Is Hiatal Hernia Repair Ever An Energency

Review Article

Which hiatal hernia's demand to be fixed? Big, pocket-size or none?

Introduction

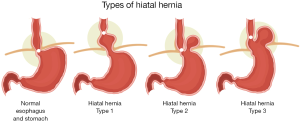

A hiatal hernia refers to herniation of intra-abdominal contents through the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm. Theories on the etiology of hiatal hernia range from esophageal shortening due to progressive acid exposure, weakness in the crural diaphragm due to aging, and longstanding increased intra-intestinal pressure from obesity or chronic lifting and straining. The prevalence of hiatal hernia varies in the literature from 15–20% in western populations (one-3). Hiatal hernias can be classified by the position of the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) and the extent of stomach that is herniated. A type I hiatal hernia occurs when there is intermittent migration of the GEJ into the mediastinum. These are frequently colloquially called "sliding hiatal hernias". Blazon I hiatal hernias make up more 95% of hiatal hernias (Figure ane) (4). They are most often asymptomatic. When symptomatic, patients volition commonly present with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (5).

Effigy 1 Diagram demonstrating hiatal hernia types 1-3.

Type II-IV hiatal hernias are commonly grouped together and chosen para-esophageal hernias (PEH) (Effigy 1). They are estimated to make upward only v–10% of all diagnosed hiatal hernias (vi). Type II hiatal hernias occur when the fundus of the tummy herniates through the esophageal hiatus. The GEJ remains normally positioned beneath the diaphragm. A type 3 hiatal hernia is a combination of a type I and type II hiatal hernia in that both the GEJ and fundus of the stomach herniate through the esophageal hiatus. A type Iv hiatal hernia occurs when there is deportation of organs other than the breadbasket into the mediastinum. Type II–IV hernias can be asymptomatic or symptomatic. Information technology has been estimated that roughly l% of patients with type II-4 hiatal hernias are asymptomatic (7).

When symptomatic, symptoms tin can be linked to gastroesophageal reflux and its complications, mechanical obstruction due to partial volvulus, or force per unit area-related symptoms caused by the herniation of organs into the posterior mediastinum. These can include regurgitation, dysphagia, early on satiety, chest pain, and shortness of jiff. Large paraesophageal hernias (PEHs) predispose to gastric volvulus with potential necrosis of the stomach secondary to impaired blood menstruation in gastric vessels (6). The potential life-threatening nature of this complication underscores the importance of determining which patients crave surgery.

The surgical management of hiatal hernia has evolved from open (transthoracic, transabdominal) procedures to laparoscopic procedures. Laparoscopy is now favored for its reduced morbidity, shorter hospital stay, and decreased pain medication requirements (8). Regardless of the approach, the aim of surgery is reduction of the hernia sac and tension-gratis closure of the hiatal defect, paired with an anti-reflux procedure.

Surgery is recommended for all acute symptomatic presentations of PEHs (obstruction or incarceration/strangulation). Management in the non-acute and asymptomatic setting is less clear. Type I hiatal hernias are not typically surgically repaired if they are asymptomatic, given their low overall morbidity. The management of type II-Iv hiatal hernia is less clear. Influential studies published more than 40 years agone led to recommendations that surgeons prophylactically repair all PEHs in gild to avoid the potential development of volvulus and/or gastric ischemia. These studies estimated a 30% or greater run a risk of developing acute symptoms and complications in "ascertainment only" patients (9,10). In recent years, however, some studies accept found that the risk of catastrophic complications is much lower than these initial estimates. This has reignited the debate on the demand to operate on asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic paraesophageal hernias (11).

Few studies have looked at the natural history of paraesophageal hernias without surgical intervention, making information technology difficult to assess the risks of watchful waiting. In order to fully identify the do good of surgical intervention, it is necessary to assess outcomes post-obit surgery with regards to symptomology, quality of life, and rates of hernia recurrence. The question of whether a patient should receive surgery is further complicated by the patient's age and medical comorbidities. It is also essential to identify special populations of patients that might have consistently worse outcomes and then that they tin be counseled on risks prior to surgery. We try to address these topics in our review of which hiatal hernias necessitate an operation.

In guild to respond the question "which hiatal hernias demand fixing," a literature search was performed using the PubMed database. Search terms included: hiatal hernia, paraesophageal hernia, diaphragmatic hernia, surgery. Abstracts were reviewed for relevancy to the topic. Studies were merely included if they were published within the last 20 years, were in English language, and the full text was available. In addition to the database search, references from each paper included were searched for eligible studies.

Management of type I hiatal hernia

Asymptomatic

Although at that place are rare reports of type I hiatal hernias leading to complications, official guidelines recommend that asymptomatic type I hiatal hernias should be observed only (12). This is because the vast majority of type I hiatal hernias do not progress to the need for emergent operation without showtime becoming symptomatic. Information technology stands to reason that if such patients accept regular follow-up, they will accept an elective repair before they develop indications for emergency surgery. At that place remains of course, the unresolved question of the natural history of type I hiatal hernias and whether they somewhen become blazon III or 4 hernias.

O'Donnell et al. observed the incidence of type I-Iv hiatal hernias in active component members of the Us. Regular army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps who served between January 2005 and Dec 2022 (2). Individuals were identified using records of inpatient and outpatient health care documented in the Defense Medical Surveillance Organization. In full, 27,276 individuals were diagnosed with a hiatal hernia during this fourth dimension period, with an overall incidence of 19.seven per 10,000 person-years. Of the 27,276 service members with a diagnosis of hiatal hernia, only 235 (0.86%). had whatever surgical repair during the surveillance period, and only 47 (0.17%) cases were emergent. This study concluded that an overwhelming majority of diagnosed cases of diaphragmatic hiatal hernia never require surgery. The true incidence of hiatal hernia in this population was likely higher, given the fact that there was no routine screening in this written report. Unfortunately, the study did not report the distribution of different hiatal hernia types in emergent and non-emergent surgeries.

Further research has examined the natural history of specifically type I hiatal hernias. A single institution retrospective review conducted by Ahmed et al. in 2022 evaluated the natural history of type I hiatal hernias less than 5 cm (13). Patients were diagnosed following endoscopy performed equally part of the workup for GERD, dysphagia, breast pain, abdominal pain, or follow-up of Barrett's esophagus. All living patients were sent a questionnaire regarding their GERD-related symptoms. Though many patients had persistent symptoms at 10 years of follow-upwardly, researchers discovered that only one.five% of patients ultimately underwent elective surgery for their hiatal hernia. Two patients received an functioning due to the development of refractory GERD. Ane patient had progressive enlargement of the hiatal hernia and underwent constituent repair secondary to the development of iron deficiency anemia. No emergency surgeries were documented over the x-year study catamenia. Given the low rate of progression to surgery, authors concluded that observation of asymptomatic small to medium sized blazon I (roman numeral) hernias is safe.

Symptomatic

There has been extensive physiologic research observing the clan between sliding hiatal hernia and gastroesophageal reflux. Scheffer et al. performed high resolution manometry and pH studies on 20 patients with a history of GERD and 20 normal volunteers during and after a standardized meal (14). They also compared the book of the intraabdominal stomach using ultrasound. Researchers noted that patients with GERD symptoms had a college proportion of time in the fasting state where they had two definitive loftier-pressure level zones on manometry consistent with the contour of a hiatal hernia (32.nine±iv.nine min h) (53.2%) compared to controls (8.7±3.iii min h) (xiv.5%) (P<0.001). Researchers too observed that when the stomach was herniated, there was a higher rate of reflux recorded on pH testing (2.i±0.half-dozen and 3.eight±0.9 per hour; P<0.05).

Furthermore, there is evidence that elective repair of type I hiatal hernia is associated with lower rates of intra and mail service-operative complications as well as decreased complication-related reoperation rates compared to PEHs (15). The causal clan between GERD and type I hiatal hernia, plus the relatively depression complication rates provide compelling testify for elective repair of these symptomatic hernias.

Management of type II-Iv PEH

Symptomatic

An platonic research written report to compare the risks and benefits of repair versus observation of symptomatic PEH would be a randomized controlled trial. However, this data is lacking given that symptomatic hernias are already routinely repaired by most surgeons. Sihvo et al. conducted one of the few studies that addresses disease-specific bloodshed of symptomatic PEHs (xi). Researchers identified 563 patients that underwent surgical treatment and 67 patients that underwent in-hospital conservative direction of PEHs from 1987–2001. They found a 2.7% perioperative mortality rate in patients who underwent surgical treatment. In patients that were hospitalized for PEH simply ultimately treated without surgery, the mortality charge per unit was 16.4%. This is probable an overestimate of bloodshed given that many patients with PEH may have never been hospitalized and thus would not be captured in the "watchful waiting" grouping of this study. Upon reviewing records for the patients that died during conservative treatment, the authors estimated that 13% of the deaths could have been prevented with surgical intervention. The results of this report highlight the poor outcomes of watchful waiting for symptomatic PEH.

In add-on to this mortality benefit, there are several well-documented symptomatic benefits to repair of PEH. Patients often report relief of their GERD symptoms: dysphagia, bloating, regurgitation and early satiety (16-18).

Additional consideration should likewise be given to improvements in cardiac and pulmonary office. Carrott et al. conducted a retrospective review comparing pre and mail service-operative pulmonary part tests (PFTs) in patients who underwent repair of either symptomatic or asymptomatic PEHs (19). The surgery group demonstrated a statistically meaning improvement in PFT values (P<0.01). Furthermore, multivariate regression models demonstrated a correlation between the degree of PFT improvement and the amount of intrathoracic stomach.

The results of this retrospective report were further corroborated in a recent prospective study of 570 patients conducted past Wirsching et al. (xx). They institute an comeback in spirometry values in 80% of patients. The degree of improvement after repair was greatest when the percentage of intrathoracic stomach was >75% (P=0.001). Depression and Simchuk also institute like improvements in spirometry values (21).

In addition to improvements in respiratory part there is also research demonstrating improvements in cardiac physiology following PEH repair (22). Cardiac MRI performed before and after a meal noted that the size of the PEH increased significantly after eating, and that this increase in size led to a concurrent decrease in left ventricular stroke volume (P=0.012) and ejection fraction (P=0.010). Post-surgical MRI showed significant improvements in left atrial and left ventricular size and EF. Pulmonary function testing was besides performed and showed improvements in FEV1 and FVC after surgery. Finally, patient reported cardiorespiratory symptoms improved afterward surgery compared to pre-operative values (P<0.01). Together, these studies show that the improvement afterwards PEH repair is not limited solely to gastrointestinal and GERD-related pathology.

Outcomes of elective repair

Current surgical techniques for elective PEH repair take documented low postoperative morbidity/mortality and favorable long-term symptomatic outcomes. Targarona et al. reported an 11% morbidity for short-term complications in their study of 46 patients with type II, 3, and 4 PEH receiving laparoscopic repair +/− mesh reinforcement and Nissen fundoplication (23). Patients were followed for a median of 24 months. This study assessed quality of life using diverse surveys: Short Form – 36 (SF-36), Glasgow Dyspepsia Severity Score (GDSS), and Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI). Quality of life according to the GIQLI was like betwixt the entire cohort and a standard comparison population. This written report found a twenty% recurrence rate over a median follow-upward of 24 months using barium swallow to make the diagnosis. The majority of recurrences were found to be asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic sliding hiatal hernias. There was no pregnant difference in patient reported quality of life betwixt groups of patients that had recurrence versus those that did non, suggesting that recurrence can be symptomatically inconsequential.

Sorial et al. conducted a retrospective review of all PEH hernia cases over a 7-yr menses, with specific attending to identifying risk factors for recurrence (24). At a median follow-up time of half dozen months, the overall symptomatic recurrence rate was 9.nine%. They examined patient demographics, hernia size, technical aspects of the operation, and surgical experience. On multivariate analysis, experience of the operating surgeon was the just gene significantly affecting the rate of recurrence.

Mehta et al. performed a pooled analysis of 20 retrospective studies. They found a pooled 5.3% intraoperative morbidity, and a 12.7% rate of postoperative complications amidst 1,387 patients undergoing laparoscopic PEH repair. Their analysis plant a sixteen.ix% recurrence rate over an adapted hateful follow-up time of 16.5 months. The recurrences were 47% type I sliding hernias, 23% wrap disruption, and 30% true PEH recurrence. The 20 studies included in their analysis had highly variable individual recurrence rates ranging from 0–44%. The authors attribute this variation in part to a heterogeneous definition of recurrence (25). Other studies have plant like favorable results (8,23,26-29).

These studies argue that constituent surgery is prophylactic and has favorable symptomatic outcomes. They also argue that run a risk of recurrence is not minimal just can be symptomatically and clinically inconsequential.

Outcomes of emergency repair

In order to decide the hazard versus benefits of elective repair versus emergency surgery, a thorough understanding of the outcomes associated with emergency repair is likewise necessary. One such report, done by Jassim et al., performed a prospective review using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database between 2006–2008 to written report 41,723 patients undergoing PEH repair in the United States (30). Emergent repair was associated with a significantly higher rate of morbidity (33.4% vs. 16.5% elective, P<0.001) and mortality (iii.two% vs. 0.37%, P<0.001) than elective repair. These differences, in part, can be explained by differing characteristics between the ii groups. Patients undergoing emergent repair were significantly more likely to exist older, male person, and to accept medical comorbidities (alcohol abuse, iron deficiency anemia, electrolyte disorders, renal failure, and weight loss/malnutrition). Patients undergoing emergent repair were also significantly less likely to receive laparoscopic surgery. After controlling for these characteristics using multivariate assay, emergency repair was associated with higher bloodshed. These results suggest that non-elective surgery leads to poor outcomes in terms of morbidity and mortality, attributable to increased age and comorbid weather condition.

Multiple other studies have shown similar results. Tam et al. used propensity score matching for gender, age, BMI, Charlson Comorbidity Alphabetize, tobacco utilize, pre-operative symptoms, hernia size, hospital, and surgeon differences betwixt constituent and emergent patients and constitute that the odds of mail service-operative complications and mortality are consistently ii–3 times greater for emergent repair versus constituent repair (31).

Ballian et al. establish that emergent presentation was associated with significant mortality even after holding other predictive variables constant. They constitute that individuals undergoing emergency PEH repair were more than likely to be male, older than 70, underweight or normal body weight, to have larger hernias, and increased comorbidities (32). In this study, mortality was 1.ane% after elective surgery versus viii.0% later non-elective surgery (P<0.01).

Polomsky et al. performed a population-based written report of admissions for PEH in the country of New York (9). Fifty-3 percent of the PEH hospitalizations in their written report were emergent. Interestingly, 66% of these were discharged before any surgical intervention. Emergency admissions had college mortality (2.vii% vs. i.two%, P<0.001), longer length of stay (7.3d vs. four.9d, P<0.001), and higher cost ($28,484 vs. $24,069, P<0.001) than elective surgery admissions (nine). Emergent presentation had statistical significance associated with mortality, length of stay, and cost in multivariable regression models including age and type of operative intervention.

Other studies have fatigued a dissimilar conclusion: that the variance in mortality between elective and emergency repair is entirely accounted for by comorbidities. Shea et al. performed a retrospective review of PEH patients at 1 institution. They compared patients undergoing emergency versus elective PEH repair, using both propensity scores and multivariate logistic regression to control for meaning differences in age, sex, body mass index (BMI), American Guild of Anesthesiology (ASA) class, tobacco use, and comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary affliction, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery affliction, and GERD. Their study identified a total of 229 patients that underwent PEH repair, with 199 undergoing elective repair (86.9%) and 30 (xiii.one%) undergoing emergent repair. Emergent cases were more probable to exist older individuals with larger and more complex hernias. They were besides more than likely to accept a longer hospital stay (6.63 vs. 2.79 days, P=0.002), more postoperative complications (44.8% vs. 19.iv%, P=0.002), and a higher proportion of severe complications. There was no statistically significant difference in readmission rates between the two groups (iii.7% vs. three.v%, P=0.22). These differences in cohorts were no longer significant when comparing propensity matched groups. This suggests that the complications experienced past the emergent group are attributable to their comorbidities and non the emergent nature of their functioning.

Augustin et al. used NSQIP data to written report 3,598 patients undergoing constituent or emergent (five%) PEH repair from 2009–2011. They similarly found that emergent surgery is non associated with mortality after adjusting for comorbidities (33). They found, instead, that frailty and preoperative sepsis increased the odds of mortality and that laparoscopic (versus open) repair and BMI ≥25 (versus BMI <18.5) were significantly protective of mortality.

Many of the higher up studies accept suggested that PEH repair in older patients is associated with greater morbidity and bloodshed. Poulose et al. specifically examined the elderly patient population (34). They used the 2005 Nationwide Inpatient Sample database to investigate octogenarians receiving elective and non-constituent surgery for PEH. Non-elective surgery was performed in 43%. Non-elective patients had college mortality (sixteen% vs. two.five%) and length of stay (xiv.3 vs. 7 days) than their constituent counterparts. This mortality is double of that presented in research without octogenarians (32). This study reported a much higher length of stay than other studies, in role because the population consisted but of octogenarians and because this study included all forms of PEH repair while other studies focus on laparoscopic approaches (35). Prolonged length of stay places patients at increased take a chance of pulmonary complications, UTI, worsening disability, and cerebral impairment in the elderly (36-39).

Together, the weight of evidence suggests that although part of the increased morbidity and mortality of emergency repair is explained past differences in comorbidities, there is also an independent risk associated with emergency repair.

Asymptomatic PEHs: elective repair versus watchful waiting

Equally the literature indicates, preventing emergency surgery for the individual patient is ideal. However, it is withal unclear the best fourth dimension to intervene electively. Mod outcomes for emergency surgery have improved, with some studies reporting bloodshed rates as low as 0–2% (27,30). With this improvement came a revisiting of the original question. Which types of hiatal hernias in which situations can effectively exist observed? What is the all-time management strategy to apply to the asymptomatic PEH population as a whole?

Modernistic population-based studies examining the disease progression of PEHs are largely lacking. In lieu of sufficient epidemiological comparisons of watchful waiting and elective paraesophageal hiatal hernia repair, research teams have turned to reckoner modeling to answer this question. Stylopoulos et al. investigated whether the risks of undergoing elective surgery to repair blazon 2 and type III hiatal hernias outweighed the risks of eventual progression necessitating functioning, or eventual farther progression necessitating emergency surgery. The research team created a Monte Carlo simulation based on a review of 1,035 patients obtained from healthcare cost and utilization projection information in 2002 (40). The principal outcome was quality adjusted life expectancy (QALE) in the 2 groups. At all fourth dimension points, watchful waiting led to a greater overall increase in QALE then elective surgery. The benefit of watchful waiting was more pronounced as age at presentation increased. This is because researchers establish that the run a risk of progression to astringent symptoms decreased as the age of the patient increased. Furthermore, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. The model was only sensitive to alterations in the mortality rates of elective and emergency operations. Given the large corporeality of data utilized to create the Monte Carlo simulation and the results of the sensitivity analysis, information technology seemed that the risks of elective PEH repair outweighed the benefits.

Sixteen years later, this study was repeated past Morrow et al. using updated outcome numbers including costs (41). A Markov decision model was developed to once more compare watchful waiting and constituent hernia repair for minimally symptomatic PEH. The model included the potential states of immediate postoperative state, PEH recurrence, symptomatic versus asymptomatic after surgery, and death. The model was synthetic based on aggregation of outcomes data from a systematic review of the literature. This was therefore a more comprehensive model than the previous study. Constituent laparoscopic hernia repair was overall more than expensive. The average cost for a patient who received constituent surgery was $11,771. For the watchful waiting arm, it was but $2,207. Patients who received elective hernia repair had an average of 1.iii additional quality adapted life years (xiv.3 vs. 13.0). The price was therefore $vii,303.00 per quality adjusted life twelvemonth. The authors note that most patients when surveyed believe that one quality adapted life year should be worth $50,000 to $100,000. Equally such, the authors conclude that cost of initial constituent surgery justified the overall comeback in quality of life.

One of the major reasons why the 2022 report differed and so strikingly from the 2002 study was that mortality of elective PEH repair has continued to decrease. The 2002 study found that the mortality associated with constituent repair was around 1%, which was the same every bit bloodshed for emergency surgery in the data they used. This repeat study in 2022 used bloodshed of around five% for emergency surgery and 0.65% for constituent surgery. Thus, just equally the sensitivity analysis in the original 2002 report predicted that changes in mortality could touch on the results of the study, these new statistics contradistinct the best decision course to again favor constituent repair.

Given this evidence, it appeared that routine operative intervention for asymptomatic PEHs would over again be recommended. Even so, an additional simulation study published by Jung et al. later in 2022 drew unlike conclusions (42). A Markov model was created based on data collected from a systematic review of studies on type 2 and 3 hiatal hernias. Researchers discovered a departure in QALE of 5 months favoring watchful waiting over elective hernia repair. Eighty-four percent of their simulations showed a more favorable issue if patients were initially assigned to watchful waiting. This result did not change in a sensitivity assay that increased the maximum age a patient could undergo surgery to 95 years. The aforementioned analysis likewise decreased the amount of years the patient was at chance for recurrence to 5 years and changed the type of closure method from mesh repair to suture simply.

It is surprising that two studies with very similar methodology yielded such strikingly unlike outcomes. Although these studies are simulations and cannot account for every variable as in a randomized controlled trial, they used the same current body of literature and statistical methodology nonetheless arrived at very dissimilar conclusions. This appears to exist due to differences in take chances percentages used in the simulations. The Jung et al. study (which favored watchful waiting) set the risk of postoperative complication subsequently emergency hiatal hernia repair to be 11.nine%. In the report by Morrow et al., the risk was set at 21%. A lower emergency complication charge per unit decreases the hazard of needing emergency surgery, favoring watchful waiting. In that location were also of import differences in the proportion of patients who progressed to a symptomatic hernia (7.4% watchful waiting study, xiii.87% elective repair written report). Finally, the Jung et al. watchful waiting study allowed for the possibility of a second constituent hernia repair, whereas the study favoring constituent repair did not. If there was a potential for multiple repairs, this would negatively impact quality of life compared to a model which didn't have this potential factored in.

All told, these studies highlight how interpretation of the literature and how changing the input data can dramatically affect the results of a Markov model. Even a sensitivity analysis will miss important differences unless every variable is examined. Therefore, without level ane evidence, it is hard to confidently derive conclusions near watchful waiting versus routine repair of asymptomatic PEHs. As such, we agree with the 2022 SAGES guidelines that controlling for the asymptomatic patient should be conducted on a case-past-case ground after discussion of the risks and benefits with the patient (12).

Assessing the risk for elective surgery

Despite the depression modern rates of morbidity and bloodshed, surgical intervention is not without complications. PEH surgery complications tin include visceral injury, vagal nerve injury, pneumothorax, and mediastinal hemorrhage, among others (28). When considering the routine repair of an asymptomatic hernia, information technology is important to place important gamble factors of the patient. This is both for optimization and for the informed consent word.

Every bit was previously mentioned, Jassim et al. institute that overall risk of complication during and post-obit elective and not-elective PEH repair was associated with chronic lung disease, electrolyte disorders, and weight loss/malnutrition. Lower rates of complication were significantly associated with female sex, elective and laparoscopic procedures (30). Increasing historic period was besides associated with an increased overall risk of complexity and mortality following elective and non-elective PEH repair.

Augustin et al. found an inverse relationship betwixt BMI and mortality. Their study found that BMI 25-50 and BMI ≥thirty (vs. BMI <18.5) were significantly protective of bloodshed (33). Frailty and preoperative sepsis increased the odds of bloodshed.

The finding from Jassim et al. for the take a chance associated with chronic lung affliction was likewise identified by other studies. Ballian et al. used stepwise logistic regression to identify variables predictive of postoperative mortality and morbidity (32). They establish peri-operative mortality was all-time predicted by history of congestive heart failure, history of pulmonary disease, age at performance (≥80 vs. <80) and urgency of operation (elective vs. emergency).

Direction of recurrent hiatal hernia

Management of the recurrent hiatal hernia is also important, given the high overall recurrence rates. Lidor et al. prospectively evaluated 101 patients who underwent elective laparoscopic PEH repair with bioprosthetic mesh. They noticed that those patients who had a return of their symptoms (dysphagia, early satiety, bloating, postprandial chest pain and shortness of jiff) tended to have a recurrent hiatal hernia greater than 2 cm based on upper gastrointestinal barium contrast exam (43). Lidor et al. therefore determined that hiatal hernias less than or equal to 2 cm were non clinically significant and should not count as a recurrence. They advocated for repair of all symptomatic recurrent hernias greater than 2 cm.

Jones et al. conducted a retrospective assay of all patients who underwent PEH repair with mesh over a 9-year menstruum (44). Lxx-nine per centum of these patients had upper GI studies post operatively to screen for radiologic recurrence. These studies were repeated annually until the patients were lost to follow-upwards. The resultant mean follow-up period was 25 months. The median size of recurrence during this follow-upward was iv cm. At that place was no significant difference in postal service-operative symptoms between patients with or without radiological occurrence.

White et al. followed 31 patients for 11.three years and found a statistically significant reduction in symptoms of dysphagia, heartburn, chest pain, and regurgitation after surgery. Patients were assessed with barium consume, and 32% of the patients were found to take recurrent hiatal hernia. Eighty percent of these recurrences were sliding hiatal hernias. The authors debate that despite the relatively high rate of recurrence of hernia overall, patients benefit symptomatically following PEH surgery, and that recurrences in the form of type I hiatal hernia practice not put the patient at increased risk for volvulus (17).

Hiatal hernia repair in special populations

Hiatal hernia repair in the elderly

Gangopadhyay et al. compared outcomes betwixt different historic period groups following laparoscopic PEH repair (35). Researchers found that older patients had a significantly higher ASA course, and required significantly longer postal service-operative length of stays. Older patients ultimately had similar long-term outcomes in terms of post-operative symptomology, recurrence and reoperation. These results propose that older patients are more vulnerable in the perioperative period, only that they are likely to accept similar long-term outcomes. Spaniolas et al. similarly concluded that while perioperative morbidity was higher in older patients, mortality did not differ between older and comparatively younger patients (45).

Interestingly, Gupta et al. made the statement that historic period and comorbidities lonely should not determine whether or not a patient received PEH repair (46). They compared outcomes between patients undergoing PEH repair and surgery for GERD to find that differences in bloodshed are better explained by perioperative pulmonary complications, venous thromboembolic events, and hemorrhage, and then they are by historic period and comorbidities. They fabricated the argument that greater focus should be spent on pulmonary optimization and prophylaxis for thromboembolic events.

El Lakis et al. evaluated 263 patients age 70 or greater and compared them with 261 younger patients. They found that patients anile 80 years or older had more comorbidities, larger hernias, increased proportion of type Four PEH, and were more probable to present emergently (47). Within this older accomplice, at that place was a statistically meaning increment in postoperative complications [45 (45%) vs. 61 (23%), P<0.001]. The majority of complications were low grade and did contribute to a longer length of stay in this elderly population. Hernia recurrence was no different in this group compared with the rest of the population. Importantly, afterwards adjustment for comorbidities, age was non a significant factor in predicting severe complications, readmission within 30 days, or early recurrence.

Staerkle et al. similarly aggregated information on 360 octogenarians and found no increased rates of intraoperative or postoperative complications, or complication-related reoperations compared with younger patients (48). Like studies have besides been conducted with smaller cohorts and found similar results (49,50). Because these studies have all institute excellent or comparable outcomes associated with PEH repair in elderly patients, nosotros believe that historic period in of itself is not a contraindication for elective surgery. Patients should be evaluated on a case by instance footing with optimization of modifiable risk factors.

Concurrent bariatric surgery and hiatal hernia repair

Hefler et al. used the metabolic and bariatric surgery quality improvement database to identify 42,732 patients who had bariatric procedures with concurrent PEH repair (51). This accomplice underwent propensity score matching in a one to one ratio to compare with patients who did not take concurrent hiatal hernia repair. Patients were excluded if they had a BMI <35. Revisional surgeries were likewise excluded. Overall, researchers institute no statistically meaning difference in 30-24-hour interval major complications or mortality between the two groups. Readmission rates were higher after concurrent PEH repair (4.0 vs. 3.6%, P=0.002). At that place were no specific increased risks with PEH repair when subdividing the bariatric surgery into sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Researchers concluded that concurrent PEH repair incurred minimal boosted risk to patients and was feasible.

Should all hiatal hernias be repaired regardless, one time in the OR?

One time in the operating room, should all hiatal hernias be repaired regardless of size or symptoms? To respond this question, a closer look at the pathophysiology of reflux is necessary. There has been a longstanding debate over the relative contribution to the anti-reflux mechanism past the diaphragmatic crura and the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). In the days of Dr. Nissen, a hiatal hernia was believed to exist a side-outcome related to an incompetent LES. A theory emerged, where prolonged esophageal exposure to acidic refluxate resulted in esophageal shortening. Dr. Nissen believed that one time the stomach was reduced dorsum into the abdomen, a fundoplication would forestall future acid exposure and esophageal shortening. In this pathophysiologic theory of GERD, the hiatal hernia repair was not an of import component of the anti-reflux functioning. Here, the diaphragm was a bystander only, and did not contribute to the GERD barrier.

An alternative viewpoint is that dysfunction of the diaphragmatic crura actively contributes to GERD, in concert with dysfunction of the LES. Both loftier resolution manometry and 3-dimensional computer modeling point towards the diaphragmatic crura and the LES contributing equally to the anti-reflux bulwark (52,53). Additionally, studies accept shown that microscopic alterations in the cyto-architecture of the diaphragmatic crura are present in those patients with GERD symptoms (54). Brute studies have shown that disruption of the diaphragm lone causes increased esophageal acrid exposure (55). Finally, a written report of healthy asymptomatic patients with small hiatal hernias still had intrasphincteric reflux and lengthening of the cardiac mucosa based on high resolution pH monitoring and biopsy (56).

It therefore stands to reason that if there are certain patients with a proclivity for the development of hiatal hernia, and if the crura is an of import component of the reflux barrier, then if a hiatal hernia is identified intra-operatively, it should be repaired, regardless of its size. This contrasts with the aforementioned bear witness that patients with clinically small hiatal hernias identified on video esophagram can be safely observed (43). Although this is true and the presence of the hernia does not necessarily indicate an firsthand demand for functioning, there is an argument that in one case the patient reaches the operating room, a repair should exist done, given the crura's important contribution to protect confronting GERD. This was demonstrated in a retrospective study comparing minimal dissection during placement of a LINX® device, and a mandatory more than extensive hiatal dissection and repair (57). In the mandatory grouping, a hiatal dissection and posterior cruroplasty was performed in all patients, regardless of whether a hiatal hernia was present. At an average follow-up time of 298 days, the minimal dissection grouping had a college incidence of hiatal hernia recurrence necessitating repair (vi.six% vs. 0%, P=0.02). Interestingly, the obligatory dissection group had a larger mean hiatal hernia size identified intraoperatively (3.95 vs. 0.77 cm). Nevertheless, these patients fared better than their counterparts who had not received the cruroplasty.

Conclusions

Although the literature is complex and occasionally alien, there are trends which emerge when the entire film is viewed from a broad perspective. Because blazon I hiatal hernias are very rarely associated with emergency complications, the literature supports only repairing those hernias which are symptomatic. For blazon Ii-IV hiatal hernias, the literature also supports repair of those hernias which are symptomatic. For hernias which are asymptomatic, the literature is alien. Equally such, the best course of action is a advisedly held discussion between patient and surgeon on the risks and benefits of constituent repair versus watchful waiting. Patients should exist optimized for surgery with careful attention to their modifiable take a chance factors. Age is non a contraindication to surgery. Concurrent hiatal hernia repair and bariatric surgery appears viable, but a higher level of evidence should exist pursued. Finally, additional population-based studies are required to make up one's mind the true incidence and ideal direction of asymptomatic hiatal hernias of all types.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was deputed by the Guest Editors (Lee L Swanstrom and Steven G. Leeds) for the serial "Hiatal Hernia" published in Annals of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgery. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE compatible disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/ten.21037/ales.2020.04.02). The series "Hiatal Hernia" was commissioned by the editorial function without any funding or sponsorship. JCL and NAB report personal fees from Ethicon, manufacturer of LINX device, outside the submitted piece of work. The authors have no other of interest to declare.

Ethical Argument: The authors are answerable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the piece of work are accordingly investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open up Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Eatables Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the commodity with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are fabricated and the original piece of work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Stål P, Lindberg Grand, Ost A, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux in good for you subjects. Significance of endoscopic findings, histology, age, and sex. Scand J Gastroenterol 1999;34:121-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O'Donnell FL, Taubman SB. Incidence of hiatal hernia in service members, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2005-2014. MSMR 2022;23:eleven-five. [PubMed]

- Gordon C, Kang JY, Neild PJ, et al. The role of the hiatus hernia in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20:719-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hyun JJ, Bak YT. Clinical significance of hiatal hernia. Gut Liver 2022;5:267-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schieman C, Grondin SC. Paraesophageal hernia: clinical presentation, evaluation, and management controversies. Thorac Surg Clin 2009;19:473-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dellaportas D, Papaconstantinou I, Nastos C, et al. Large Paraesophageal Hiatus Hernia: Is Surgery Mandatory? Chirurgia (Bucur) 2022;113:765-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carrott Pow, Hong J, Kuppusamy Thousand, et al. Clinical ramifications of giant paraesophageal hernias are underappreciated: making the case for routine surgical repair. Ann Thorac Surg 2022;94:421-six; discussion 426-viii. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Diaz S, Brunt LM, Klingensmith ME, et al. Laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair, a challenging operation: medium-term outcome of 116 patients. J Gastrointest Surg 2003;seven:59-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Polomsky M, Hu R, Sepesi B, et al. A population-based analysis of emergent vs. elective hospital admissions for an intrathoracic stomach. Surg Endosc 2010;24:1250-v. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Skinner DB, Belsey RH. Surgical management of esophageal reflux and hiatus hernia. Long-term results with i,030 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1967;53:33-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sihvo EI, Salo JA, Räsänen JV, et al. Fatal complications of adult paraesophageal hernia: a population-based written report. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;137:419-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kohn GP, Cost RR, DeMeester SR, et al. Guidelines for the management of hiatal hernia. Surg Endosc 2022;27:4409-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahmed SK, Bright T, Watson DI. Natural history of endoscopically detected hiatus herniae at late follow-upwards. ANZ J Surg 2022;88:E544-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scheffer RC, Bredenoord AJ, Hebbard GS, et al. Outcome of proximal gastric volume on hiatal hernia. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010;22:552-6, e120.

- Köckerling F, Trommer Y, Zarras Thou, et al. What are the differences in the result of laparoscopic axial (I) versus paraesophageal (Two-4) hiatal hernia repair? Surg Endosc 2022;31:5327-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lidor AO, Steele KE, Stalk Yard, et al. Long-term quality of life and gamble factors for recurrence after laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. JAMA Surg 2022;150:424-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- White BC, Jeansonne LO, Morgenthal CB, et al. Do recurrences later on paraesophageal hernia repair thing?: Ten-year follow-up after laparoscopic repair. Surg Endosc 2008;22:1107-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rathore MA, Andrabi SI, Bhatti MI, et al. Metaanalysis of recurrence later on laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. JSLS 2007;11:456-60. [PubMed]

- Carrott Pow, Hong J, Kuppusamy One thousand, et al. Repair of giant paraesophageal hernias routinely produces improvement in respiratory part. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2022;143:398-404. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wirsching A, Klevebro F, Boshier PR, et al. The other explanation for dyspnea: giant paraesophageal hiatal hernia repair routinely improves pulmonary role. Dis Esophagus 2022; [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Low DE, Simchuk EJ. Effect of paraesophageal hernia repair on pulmonary function. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;74:333-7; discussion 337. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Milito P, Lombardi M, Asti E, et al. Influence of large hiatus hernia on cardiac volumes. A prospective observational cohort study by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Int J Cardiol 2022;268:241-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Targarona EM, Novell J, Vela S, et al. Mid term analysis of prophylactic and quality of life after the laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hiatal hernia. Surg Endosc 2004;18:1045-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sorial RK, Ali M, Kaneva P, et al. Modern era surgical outcomes of elective and emergency behemothic paraesophageal hernia repair at a high-volume referral center. Surg Endosc 2022;34:284-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mehta Southward, Boddy A, Rhodes One thousand. Review of effect later on laparoscopic paraesophageal hiatal hernia repair. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2006;16:301-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Velanovich V, Karmy-Jones R. Surgical management of paraesophageal hernias: upshot and quality of life assay. Dig Surg 2001;xviii:432-seven; discussion 437-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pierre AF, Luketich JD, Fernando HC, et al. Results of laparoscopic repair of giant paraesophageal hernias: 200 consecutive patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;74:1909-15; give-and-take 1915-6.

- Andujar JJ, Papasavas PK, Birdas T, et al. Laparoscopic repair of large paraesophageal hernia is associated with a low incidence of recurrence and reoperation. Surg Endosc 2004;18:444-seven. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Targarona EM, Grisales South, Uyanik O, et al. Long-term outcome and quality of life afterward laparoscopic treatment of large paraesophageal hernia. World J Surg 2022;37:1878-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jassim H, Seligman JT, Frelich G, et al. A population-based assay of emergent versus constituent paraesophageal hernia repair using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Surg Endosc 2022;28:3473-eight. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tam V, Luketich JD, Winger DG, et al. Non-Elective Paraesophageal Hernia Repair Portends Worse Outcomes in Comparable Patients: a Propensity-Adjusted Analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 2022;21:137-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ballian N, Luketich JD, Levy RM, et al. A clinical prediction rule for perioperative bloodshed and major morbidity after laparoscopic giant paraesophageal hernia repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2022;145:721-nine. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Augustin T, Schneider Due east, Alaedeen D, et al. Emergent Surgery Does Not Independently Predict 30-24-hour interval Bloodshed After Paraesophageal Hernia Repair: Results from the ACS NSQIP Database. J Gastrointest Surg 2022;19:2097-104. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Poulose BK, Gosen C, Marks JM, et al. Inpatient mortality assay of paraesophageal hernia repair in octogenarians. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;12:1888-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gangopadhyay N, Perrone JM, Soper NJ, et al. Outcomes of laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair in elderly and high-take a chance patients. Surgery 2006;140:491-eight; discussion 498-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kheterpal S, Tremper KK, Heung M, et al. Development and validation of an acute kidney injury gamble index for patients undergoing full general surgery: results from a national data set. Anesthesiology 2009;110:505-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smetana GW, Lawrence VA, Cornell JE. Preoperative pulmonary take chances stratification for noncardiothoracic surgery: systematic review for the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:581-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paredes S, Cortinez Fifty, Contreras 5, et al. Post-operative cognitive dysfunction at 3 months in adults later non-cardiac surgery: a qualitative systematic review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2022;threescore:1043-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Witlox J, Eurelings LS, de Jonghe JF, et al. Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2010;304:443-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stylopoulos Northward, Gazelle GS, Rattner DW. Paraesophageal Hernias: Functioning or Observation? Annals of Surgery 2002;236:492-500. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morrow EH, Chen J, Patel R, et al. Watchful waiting versus constituent repair for asymptomatic and minimally symptomatic paraesophageal hernias: A price-effectiveness analysis. Am J Surg 2022;216:760-iii. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jung JJ, Naimark DM, Behman R, et al. Approach to asymptomatic paraesophageal hernia: watchful waiting or constituent laparoscopic hernia repair? Surg Endosc 2022;32:864-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lidor AO, Kawaji Q, Stem M, et al. Defining recurrence afterwards paraesophageal hernia repair: correlating symptoms and radiographic findings. Surgery 2022;154:171-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones R, Simorov A, Lomelin D, et al. Long-term outcomes of radiologic recurrence after paraesophageal hernia repair with mesh. Surg Endosc 2022;29:425-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spaniolas K, Laycock WS, Adrales GL, et al. Laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: advanced age is associated with modest simply non major morbidity or mortality. J Am Coll Surg 2022;218:1187-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gupta A, Chang D, Steele KE, et al. Looking beyond historic period and co-morbidities every bit predictors of outcomes in paraesophageal hernia repair. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;12:2119-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- El Lakis MA, Kaplan SJ, Hubka M, et al. The Importance of Age on Short-Term Outcomes Associated With Repair of Giant Paraesophageal Hernias. Ann Thorac Surg 2022;103:1700-ix. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Staerkle RF, Rosenblum I, Köckerling F, et al. Outcome of laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair in octogenarians: a registry-based, propensity score-matched comparison of 360 patients. Surg Endosc 2022;33:3291-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khoma O, Mugino 1000, Falk GL. Is repairing behemothic hiatal hernia in patients over fourscore worth the risk? Surgeon 2022; [Epub ahead of impress]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hazebroek EJ, Gananadha Due south, Koak Y, et al. Laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: quality of life outcomes in the elderly. Dis Esophagus 2008;21:737-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hefler J, Dang J, Mocanu V, et al. Concurrent bariatric surgery and paraesophageal hernia repair: an assay of the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Clan Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP) database. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2022;15:1746-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pandolfino JE, Kim H, Ghosh SK, et al. High-resolution manometry of the EGJ: an analysis of crural diaphragm function in GERD. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:1056-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yassi R, Cheng LK, Rajagopal Five, et al. Modeling of the mechanical function of the homo gastroesophageal junction using an anatomically realistic three-dimensional model. J Biomech 2009;42:1604-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zifan A, Kumar D, Cheng LK, et al. Three-Dimensional Myoarchitecture of the Lower Esophageal Sphincter and Esophageal Hiatus Using Optical Sectioning Microscopy. Sci Rep 2022;7:13188. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mittal RK, Sivri B, Schirmer BD, et al. Upshot of crural myotomy on the incidence and mechanism of gastroesophageal reflux in cats. Gastroenterology 1993;105:740-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robertson EV, Derakhshan MH, Wirz AA, et al. Hiatus hernia in salubrious volunteers is associated with intrasphincteric reflux and cardiac mucosal lengthening without traditional reflux. Gut 2022;66:1208-xv. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tatum JM, Alicuben Due east, Bildzukewicz N, et al. Minimal versus obligatory dissection of the diaphragmatic hiatus during magnetic sphincter augmentation surgery. Surg Endosc 2022;33:782-eight. [Crossref] [PubMed]

doi: 10.21037/ales.2020.04.02

Cite this commodity as: Dunn CP, Patel TA, Bildzukewicz NA, Henning JR, Lipham JC. Which hiatal hernia'southward need to be fixed? Large, small or none? Ann Laparosc Endosc Surg 2022;5:29.

Is Hiatal Hernia Repair Ever An Energency,

Source: https://ales.amegroups.com/article/view/5885/html

Posted by: looneysamet1997.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Is Hiatal Hernia Repair Ever An Energency"

Post a Comment